As I scrolled through my daily readings on my phone I came across an image that confused me: Mexico City’s iconic Ángel de la Independencia statue surrounded by a sea of people with the buildings around it burning in the background. At first I wondered, why are there people all around the monument? (This is strange because the monument is at the center of a large intersection and it is usually surrounded by cars and the Distrito Federal’s typical green and white taxis). Of course, in our days seeing tall office buildings and skyscrapers in flames are images that carry a heavy visual burden. Since the text that accompanied the image was too small to read at first glance on my phone all I could take in was the image. Was this a protest? I didn’t see any signs or flags. I clicked the  image to find that it is a poster for the upcoming film World War Z. There was not much to the accompanying article. It only mentioned that there was a series of new posters promoting the movie with aerial photos of cities across the globe being overrun with zombies, not protesters. The inclusion of Mexico City and the Ángel de la Independencia among the other cities (Berlin, Rome, Sydney, Paris and New York) was interesting to me. This puts Mexico City, at least visually, on level with the European cities. It is an equal target of post-human decemation. It is a «civilized space» that can fall to barbarism. While its inclusion on the short list of cities to be destroyed by zombies can be explained by the fact that it promotionally make sense because there is a huge number of people both in the US and across the world that will recognize the Ángel de la Independencia, it is also interesting to consider some other readings of the image.

image to find that it is a poster for the upcoming film World War Z. There was not much to the accompanying article. It only mentioned that there was a series of new posters promoting the movie with aerial photos of cities across the globe being overrun with zombies, not protesters. The inclusion of Mexico City and the Ángel de la Independencia among the other cities (Berlin, Rome, Sydney, Paris and New York) was interesting to me. This puts Mexico City, at least visually, on level with the European cities. It is an equal target of post-human decemation. It is a «civilized space» that can fall to barbarism. While its inclusion on the short list of cities to be destroyed by zombies can be explained by the fact that it promotionally make sense because there is a huge number of people both in the US and across the world that will recognize the Ángel de la Independencia, it is also interesting to consider some other readings of the image.

The construction of the Ángel de la Independencia was commissioned by Porfirio Díaz in 1902 and was carried out by Antonio Rivas Mercado and Enrique Alciati. The monument was to commemorate the centenary of Mexico’s independence from Spain and was inaugurated on September 16th, 1910. The monument, along with many other architectural projects carried out during Porfirio Díaz’s regime (known as the Porfiriato, 1876-1911), were part of his plan to modernize Mexico (well, at least Mexico City). Artistically this was accomplished by reproducing European styles that gave the  city the appearance of modernity (Paris being their model). This visual connection with Europe is reproduced in World War Z‘s promotional posters. So when we see the Ángel de la Independencia overrun with the living dead how are we to interpret this image? Has the façade of modernity finally been overtaken by Mexico’s «barbaric» past in the form of the reanimated dead? Are Moctezuma or Cuauhtémoc there among the walking dead consuming the inhabitants of the city? Is the zombie horde a revolutionary force fighting for a new form of independence?

city the appearance of modernity (Paris being their model). This visual connection with Europe is reproduced in World War Z‘s promotional posters. So when we see the Ángel de la Independencia overrun with the living dead how are we to interpret this image? Has the façade of modernity finally been overtaken by Mexico’s «barbaric» past in the form of the reanimated dead? Are Moctezuma or Cuauhtémoc there among the walking dead consuming the inhabitants of the city? Is the zombie horde a revolutionary force fighting for a new form of independence?

The zombie pandemic (as it is used in WWZ – disclaimer: I am talking only about the film since the book is very different) is a global event but apparently it is worse in globalized spaces such as New York, Paris or Mexico City. The accumulation of people in these urban centers makes them all the more dangerous. While in the past of zombie films the isolated countryside was the worst place to be (George A. Romero‘s original Night of the Living Dead was so scary because there was no where to go) in more recent zombie fiction we see that suburbs and cities are the places to avoid (the characters of The Walking Dead have terrible experiences in Atlanta and avoid «civilized» groups as much as possible). The imagined destruction of major urban spaces in the form of zombie apocalypse can be read as some sort of inherent impulse in the body that needs to re-create society. The human body is now incapable, even in death, to support the economic, political and social demands of our current globalized situation. In the trailer for WWZ they say that when it comes to the end it is time to think about the beginning. In a summer full of apocalyptic and post-acpocalypic films (ranging from After Earth and Oblivion to This Is The End) there is a repetitive imagining of endings and beginnings and WWZ bases these endings around images of modernity and civilization.

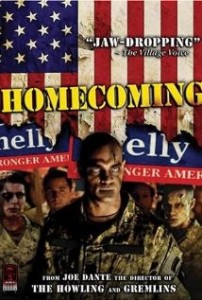

To take this reading to a more critical level we can consider Jens Andermann‘s ideas about visual regimes in his book The Optic of the State: Visuality and Power in Argentina and Brazil. If we consider the Ángel de la Independencia as a hegemonic visual text that in some way validates certain political/state ideas and histories (Mexico’s independence from Spain, Porfirio Díaz’s government, the continuity of Mexico’s sovereignty, etc.) then its destruction is an erasure of history and of state power. The fragility of the nation is in question. These zombie hordes, that appear at first glance like protesters that we are seeing increasingly around the world (like those currently in São Paulo), show how re-appropriating urban spaces or using them in new ways can lead to a collapse of society. In other words, we are one pandemic away from being hunters and gatherers and civilization as we know it is hanging by a thread. Zombie films have always had a political critique but as the zombie threat moves from George A. Romero’s rural setting to WWZ’s globalized urban  pandemic the visual message becomes clear (I would say that the political messages in zombie films are consistently visual, from the civil rights message of The Night of the Living Dead to the geo-political and necro-political implications of WWZ): the nation/state needs reset and it is an impulse that transcends life. The disappeared dead, the neglected poor, the sacrificed solider (this is portrayed in the episode of Masters of Horror titled «Homecoming») all reappear to rampage the city.

pandemic the visual message becomes clear (I would say that the political messages in zombie films are consistently visual, from the civil rights message of The Night of the Living Dead to the geo-political and necro-political implications of WWZ): the nation/state needs reset and it is an impulse that transcends life. The disappeared dead, the neglected poor, the sacrificed solider (this is portrayed in the episode of Masters of Horror titled «Homecoming») all reappear to rampage the city.

Another approach could be through Slavoj Zizek‘s book titled Violence. Zizek deals in terms of objective and subjective violence that create apparently irrational outburst of mass violence. The explanation for this, according to Zizek, is that societies create the conditions for these outburst on a daily basis with the low-level violences it inflicts on its citizens. The violent condition of life in contemporary society is the very cause of the zombie apocalypse and this has been the case since Romero’s radioactive space explosion that initially reanimated his dead. When we see the Ángel de la Independencia within its monstrously urbanized backdrop we can consider that the zombie horde is reacting and responding to the last 103 years of daily violence that the angel’s golden eyes have witnesses from her corinthian perch.

As we see this series of promotional pictures for WWZ we can ask, «Why do we keep imagining the destruction of society and civilization?» and «What does it mean that these zombie attacks are focused on symbols of national and historical significance?» The destruction of Mexico City in these images strangely places Mexico City on a first world level with Berlin, Paris or Sydney but at the same time destroys its new found status.

Un comentario

Aunque encuentro interesante la lectura que haces acerca del Ángel de la Libertad, creo que es necesario ver el afiche dentro del contexto de producción, es decir, tomando en consideración los otros afiches que lo acompañan, para ver otros puntos que se vuelven aún más interesantes. Si vemos por ejemplo las dos naciones Latinoamericanas retratadas en los afiches, podemos ver que lo que sobresale en el afiche son figuras religiosas (el ángel junto al Cristo Redentor de Rio), ambos monumentos establecidos en un una época de modernización de cada país pero con la fuerte influencia católica que nunca logró separarse del todo del estado. Y cuando vemos a las ciudades repletas de muertos vivientes (que a todo esto se ven muy mal en los afiches, pésimo CGI) lo único que sobresale son estás imágenes de religiosidad y modernización, lo único que sobrevive al colapso de la sociedad, los demás edificios están en llamas, incluso la naturaleza misma, pero la fuerza de estas imágenes religiosas conservan incluso un halo de luz que los trae a primer plano. Cabe preguntarse entonces ¿Podrías haber reconocido a Ciudad de México sin su ángel?