The debate surrounding homeless encampments begs the question: who has a right to the city?

The ongoing coronavirus pandemic has laid bare deep social and racial inequities across the U.S. In Austin, the homeless encampments in freeway underpasses, parks, and traffic islands show the rapid increase of urban poverty–a contemporary form of structural violence.

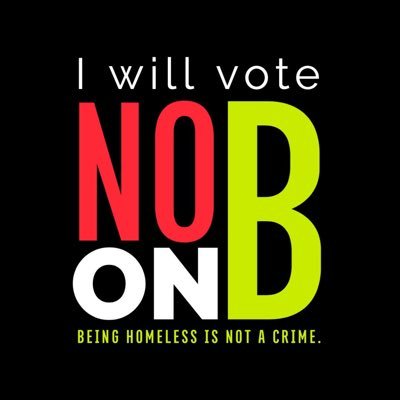

The citywide proposition known as Proposition B is a petition-driven response to these homeless encampments. It seeks to criminalize three behaviors associated with homelessness: sitting or lying down on public sidewalks or sleeping outdoors, panhandling, and camping in undesignated public areas. These behaviors were decriminalized in summer 2019 after over a year of community pressure by the #HomesNotHandcuffs coalition. Now, some residents want to reverse the city’s course and invisibilize the poorest people in Austin.

Supporters of Prop B believe the answer to dealing with people experiencing homelessness is for the police to issue them citations, arrest them, and incarcerate them. The consensus among those seeking to bring back the city’s anti-camping laws is that “skyrocketing crime” is happening in and around Austin’s homeless encampments. For example, the campaign website of Save Austin Now features testimonies of witnesses and survivors of violent street encounters, indecent exposure, and drug use in public. The rallying cries from supporters of the anti-camping law, such as «Take back our city!» and «Take back our parks!,» speak volumes. Who is this “our” they speak of? People born in Austin? “Taxpayers”? Citizens? This question brings us to the crux of the debate on anti-camping laws: To whom does the city belong?

It’s no secret that Austin has catered most of its recent urban development to the affluent techies, middle-class hipsters, and other millennial professionals driving the gentrification that is transforming the city’s neighborhoods. Last year, when the city approved the redevelopment of five student housing apartment complexes on Riverside Drive into a major mixed-use development, Austin sent the message that urban stylized renewal is intended for a privileged, monied public. Now that homeless encampments have appeared across multiple traffic islands on Riverside Drive, Prop B is precisely the kind of legislative tool required to consolidate the city’s patterns of exclusive urban development and displacement of the economically disadvantaged.

On-the-ground participatory action research by Ground Theater and Grassroots Leadership has found that “criminalization is harmful and ineffective at connecting folks experiencing homelessness to housing supports.” That’s why pressuring the city to maintain its decriminalization of homelessness is crucial. Exercising our right to vote and intervening in urban policy and planning is a means of social transformation, but it’s not our only option. Vote «No» on Prop B, but don’t stop there.

Homelessness will not end by policing our way out of it. Expand your ideas of who forms part of “our” community. Imagine anti-carceral solutions, beyond criminalization and banishment. Refuse the alluring myth of urban enclaves devoid of wretched living conditions on the streets. And reckon with the insight of Haitian-American writer Edwidge Danticat, who said: «The poor in the richest country in the world should not be poor at all. They should not even exist.»

Michael Reyes Salas is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Texas at Austin, where he

earned his PhD in Comparative Literature. He is an interdisciplinary scholar who studies the

intersection of race, criminalization, and visual cultures of imprisonment.

Photo credits of featured image: Austin-American Statesman